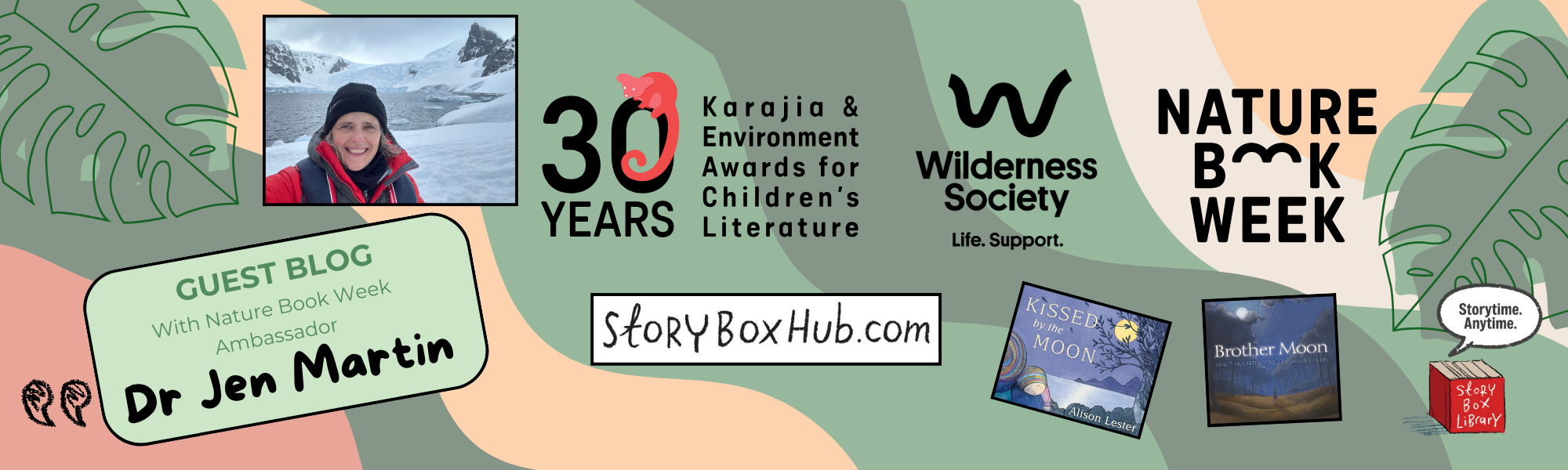

Q&A with Nature Book Week Ambassador, Dr Jen Martin

18 Oct 2024

Dr Jen Martin, Nature Book Week Ambassador, can you tell us about yourself, and your integral role at the University of Melbourne, as its founder of the Science Communication program?

I was really fortunate to spend a lot of time in nature growing up. My dad was a researcher working on frogs, and I got to help him. It’s not surprising then that I ended up doing a PhD in zoology. I'd grown up seeing that nature didn't have its own voice, and humans were having such a massive negative impact on the planet. I wanted to be part of that amazing group of people working towards conserving biodiversity. You can't protect something if you don't understand it. During my PhD, I was so excited about the work I was doing, but I felt like the academic system—publishing papers, attending conferences, building an academic track record—didn’t fulfil my need to make a difference in the real world in protecting nature. I didn't have the skills to communicate what I was learning outside academic circles; let alone to different audiences. I began a whole different journey to what I expected, and it led me to not only improve my own communication skills, but help other scientists share science with all sorts of different audiences. Science is relevant to everybody!

You worked as a field ecologist before entering into the tertiary world, can you tell me about what this role entailed and how it shaped your understanding, beliefs and misconceptions about the world and environment around us?

I spent seven years, across honours and my PhD working in patches of forest in northeastern Victoria. My work involved really trying to understand in great detail two different populations of these particular possums called bobucks. I looked at their health, aging, growth of the young and genetic work to see the relationships between individuals in the two populations. I was really seeing the forest through the eyes of a possum. Watching so closely what they were doing and how they were interacting with one another, and really getting to know every inch of these patches of forest, knowing—and measuring—every tree.

Can you tell us about your book? Why am I like this and what inspired you and what you hope readers will take from it?

Why am I like this actually started on the radio. Every Wednesday morning I go into the studio at RRR in Melbourne. I have a 15 minute science segment called Weird Science. I get to pick any topic that I think will get a breakfast radio audience interested in science. A lot of that ends up being sort of popular psychology stuff. Then I started writing up little blog posts about them, because people used to ring the studio all the time and say, ‘how can I find out more information about that?’ And my job is to make the information easy to read and accessible, but 100% based on accurate information. The book really is just a collection of stories that started as radio stories. And what I hope is that it’s a public service announcement that says to the reader: whatever you're worried about, in whatever way you feel that you're weird or different or strange: yes, you are, but so are the rest of us. There are really good reasons as to why we feel those things or do those things or behave in those ways. The book covers everything from: why do people stick their tongue out to when they're concentrating? Why can't we stop taking photos on our phones? Why do we get songs stuck in our heads? Why is it that we walk through a doorway and can't remember why we're in the room—it's not a sign of early onset dementia. This is the psychology or the neuroscience or the behavioral science behind why we do those things. And it's just been such a joy to share with people.

Why do you think events like Nature Book Week are essential?

The Wilderness Society’s Nature Book Week (14–20 October) reminds us of how central both nature and books are to our wellbeing. People need nature. People need to spend time in nature. There's so much research that shows having time in green spaces, even if they're small, urban green spaces, makes us both physically and mentally well. And of course, we also know that reading—not just for children, but for adults—feeds our souls. Reading gives us the ability to see the world through different eyes, to experience the world in so many different ways. When you bring those two things together, it's kind of an unstoppable force, because, of course, it's a great privilege to be able to actually spend time in truly wild areas. But many of us will never do that, or certainly won't get to do that very often. Instead, books can take us there—they help us to be in beautiful wild places and see the world through the eyes of whoever the characters are, whether they be people or plants or animals. Stories transport us and fill our need for connection in all sorts of fundamentally important ways.

Books about nature help us to value nature, and it's only through valuing nature that we can all do better to conserve nature.

Two of my favourite children’s books (from past Nature Book Week shortlisted books) have moon in the title:

Brother Moon by Maree McCarthy Yoelu and Samantha Fry; published by Magabala Books, shortlisted for the Wilderness Society’s 2021 Environment Award for Children’s Literature. I love this powerful tale of connection to Country. Great-Grandpa Liman tells the story to his great-grandson of this mysterious brother who guides him on his hunting and fishing trips. The illustrations are superb, and reading the story feels like you’re sitting by the campfire listening to Great-Grandpa Liman too. Alison Lester’s Kissed by the Moon published by the Penguin Group. Shortlisted for the Wilderness Society’s 2014 Environment Award for Children’s Literature. Part poem, part lullaby, this gentle story celebrates a baby’s wonder at this beautiful world and reminds us that nature is all around us. Each reading makes my heart burst and this is the book that I have given to every friend who has had a baby over the last ten years!

The StoryBox team wish to thank Dr Jen Martin, Nature Book Week Ambassador, along with Lily and Gen from the Wilderness Society for making this Q&A possible.